In Memory

|

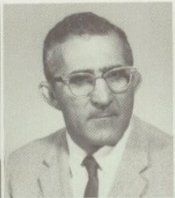

Morris Aronson Feb. 14, 1916 - Dec. 22, 2006

SOUTH BEND - Morris "Moe" Aronson, 90, of South Bend died at 2:05 p.m. Friday, Dec. 22, in St. Paul's Retirement Community following an illness. Mr. Aronson was born Feb. 14, 1916, in Chicago, IL, to the late Samuel and Anna (Kruveshevsky) Aronson and was a lifetime South Bend resident. In 1942, he married Sarah "Sally" Rosen, who preceded him in death in 1970. He was also preceded in death by two brothers, Eli and Jack Aronson. On Nov. 29, 1975, in South Bend he married Marian E. Marty Camblin, who survivies. Al so surviving are his daughter, Jane (James) Skaggs of Vernon Hills, IL; his son, Michael Aronson of Indianapolis, IN; his stepdaughter, Mary Ellen Delgado of South Bend; two stepsons, John M. (Ann) Camblin of North Liberty, IN, and Mark L. (Sharon) Camblin of Knoxville, TN; five grandchildren, Brian (Maureen) Skaggs, Sara Skaggs, Julia (John) Goetzka, John W. (Gretchen) Camblin and Peter (Jill) Martin; and three great-granddaughters, Olivia Camblin, Katja Goetzka and Catherine Martin. Moe retired as a math teacher with the South Bend Community School Corporation in 1984, after 46 years, primarily at John Adams High School . He continued teaching as a substitute teacher for many years in area schools following retirement. He was a well-known wrestling and assistant football coach at Adams and led the wrestling team to the state title in 1966. He was a 1934 graduate of the former South Bend Central High School and received bachelor of science degrees in mathematics and chemistry from Purdue University in 1939. He then went on to receive his masters degree in Physical Education. In 1935, he served a year in the Civilian Conservation Corps, at Pulaski State Park . He enlisted in the United States Army in 1943, and was discharged as a first lieutenant after serving in the 10th Mountain Division during World War II. He was a member of the Michiana YMCA for 79 years, where he worked out religiously and was an avid handball player. Moe was honored for his hard work and dedication by being enshrined in the Indiana Wrestling Hall of Fame and the South Bend City Hall of Fame. He will be loved and remembered for his sense of humor and zest for life, and will be missed by all those who have been fortunate enough to have known him. Funeral services will be conducted at 11 a.m. Wednesday, Dec. 27, in the Welsheimer Family Funeral Home, 521 N. William St. Burial will follow at Southlawn Cemetery. Friends may call from 4 to 8 p.m. Tuesday, Dec. 26 in the funeral home. In lieu of flowers, memorial contributions may be made to the YMCA of Michiana, 1201 Northside Blvd., South Bend, IN 46615. Family and friends may leave e-mail condolences at welshfh@yahoo.com. |

|

| December 26, 2006 David Rumbach Tribune Staff Writer | |

|

SOUTH BEND -- Morris "Moe'' Aronson, who died Friday at age 90, inspired students as a talented math teacher and hard-nosed wrestling coach at Adams High School for nearly five decades. |

|

No ordinary MoeAronson knew when to be toughJACOB SANDOCK Tribune Staff Writer January 7, 2007 In 1988 as a freshman at the Rabbi Naftali Riff Yeshiva and having taken a hard knee while attempting a lay up -- in a most unprotected spot -- I crumpled into a ball in the school gymnasium and whimpered under the basket as my classmates gathered around me with growing concern. Morris "Moe" Aronson, the longtime wrestling coach and math teacher at Adams High School -- who conducted gym classes for one semester at the South Bend High School/Rabbinical College -- ambled over to the scene on his replacement hips, assessed the situation with an intense, surgical calm and then began to methodically clear away the crowd. "Step aside, men! Step aside!" Moe barked with his signature semi-lisp while grabbing at jerseys; his face curled into an unconcerned scowl. Well, it sure didn't feel OK. And Moe's spot-on diagnosis of the situation did little to ease the pain. But for this Tribune reporter, that moment was captured with Kodak clarity; every gesture and word Moe produced in his somewhat comical dismissal of my "situation" a calculated message, no doubt, aimed at our class. The message, clearly, that whatever beats you down to the ground is insignificant; that the pain is insignificant, and that, ultimately, moving past what felled you and rising up is all that matters. It was a message Moe, who died recently at 90 years old, passed on, in different ways, to myriad others throughout his life and during his 46 years as an educator and 22 years as the wrestling coach at Adams. As a fitness guru Moe was unrelenting. He was a member of the Michiana YMCA for 79 years and was, physically, the stuff legends are made of. It is said that he used to ride his bike to Benton Harbor, used to jog to Elkhart just for the fun of it. As a man, he was tougher than leather, softer than suede and a loving husband to his wife, Marty. But as an educator and coach, Moe reached the highest pinnacle. He touched the lives of young people who knew opportunity and he saved the lives, literally, of underprivileged young people to whom "opportunity" had always been just another word. "I tell everybody that I know that had it not been for Moe Aronson I would be either dead or in prison," said Norval Williams. With Moe's help, Williams went on to serve his country in Vietnam and to then spend nearly 28 years serving the community with the South Bend Police Department as a Lieutenant and public information officer. "Moe was a good, good man and he coached me all the way down to the (wrestling) state finals my last two years at Adams in 1962 and 1963. He rode herd on me as if he was my father and I always looked up to him as if he was my father. Even though my own father was a fine, fine man. Moe was it. "I think what Moe did was that if he had seen somebody who had the potential to go off in the wrong direction, he would always kind of step in. He wanted you to be tough on the mat, but not to be a tough guy on the streets because you could get killed on the streets. And you were not going to get killed on the mat. Any frustration you had, he wanted you to take it out on the mat and use that energy for something." According to Williams, Moe looked for potential in kids where others might not see it and had a style all his own, based on toughness and measured doses of intimidation, in trying to bring it out. Moe's self-described "Mean face" was an educational tool, and he knew how to use it. "He caught me and a friend coming out of a liquor store one night, as teenagers would do back then," said Williams, "and Moe caught me in the hallway at Adams and, right in front of all my friends, slammed me up against the wall, hard, real hard, and he told me, 'If I ever ever see you coming out of another saloon, I will beat you. You understand that? I will beat you.' All I could say was 'Yes sir.'" Probably safe to say that this type of disciplinary action would not fly in today's educational climate. But for Williams, in that time and place, it was just what the doctor ordered. "To this day I still don't drink," said Williams. "I am proud to have been associated with him. I loved him with all my heart and I miss him. He was like part of my family." John Mosby's story is strikingly similiar. Mosby, a South Bend native who attended Jefferson Middle School and Adams, heads his own private law practice in Denver these days. But it was not long ago that he was, in the eyes of some (not to Moe), just another black kid from the streets. "I would re-write the Bible if I could and in place of 'But for the grace of God, there goes I,'" said Mosby, "I would write: 'But for the grace of Moe, there goes I.' He is the most instrumental person in my life. As you go though life you think back on the people you've met. And some people are just an afterthought. But there are other people who become institutions in your life. And Moe was that type of person." Mosby, who a couple of years ago won the largest class action suit in the history of the federal government (Glover/Albrecht v. Potter), won a state wrestling championship in 1966 under Moe's tutelage. But Moe's influence, he said, extended far beyond the mat. "He was just a breath of fresh air," said Mosby. "He loved the underdog and he was always trying to help you. He always tried to convince you that you had the ability. Moe could see your capacity and he drove you to your capacity. Never over it and never under it. "When you come through life, before you can believe in anything you have to believe in yourself. And he motivated you to believe in yourself. Then, with that belief, you start to believe in other things." Moe not only carved Mosby into a winner on the mat, but into an overall winner; someone who learned to believe in himself where others did not. And there was nothing hands-off when it came to Moe's mentoring. Moe hit the mat with Mosby and his other wrestlers in practice and he hit the road with them when they needed his help. "He actually drove me down to Indiana State University (in Terre Haute)," said Mosby of Moe's post-high school influence. "He drove me down there and helped me to get in to college and that's where I graduated. He was just such a special person." "I think Moe felt that everything in life had to be addressed," said local attorney Jim Groves, who wrestled for Moe and grew up with his son, Michael. "If he thought you were someone who would help yourself," Groves said, "then he would help you help yourself. (Norval and John) are two classic examples of how a good teacher can take a young man and mold him into his potential. "Nobody to Moe was a stranger in the halls where he taught. If he thought someone drew his attention and something needed to be corrected, he stepped in and corrected it. Now that takes guts. That type of guts is something that we all could use a little bit more of today, instead of always looking over our shoulders and wondering, 'what are going to be the repercussions of my standing up for my own principles?' Moe never worried about the repercussions. He knew what his principles were and he felt it his duty in life to convey those principles to others." "He just had a great heart," said Moe's wife, Marty, who also served as a local educator for a number of years and shared Moe's passion for physical fitness. "And he cared for people. I admired him because of his ways; his tenacity and intelligence. He was just a wonderful person to live with. I loved him to pieces." So did many others. There are not enough columns in the newspaper or words in the dictionary to describe a guy like Moe. Which is of little effect to Mosby, considering that words have little to do with his story. "Moe's life spoke for itself," Mosby said. "He said it all by the way he lived." |

|